Here is another cross-post from my daily blog about the First World War and the birth of our modern world in blood and fire.

08 February 1915 – Birth Of A Nation

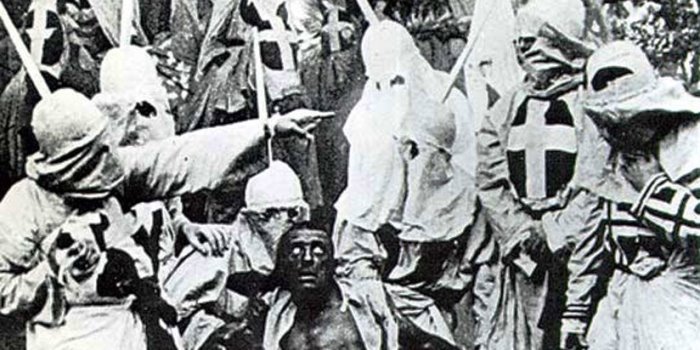

A century ago today, the most racist movie ever made is shown to the public for the very first time at Clune’s Auditorium in Los Angeles. Based on, and originally named for, Thomas Dixon’s novel and play The Clansman, it is simultaneously one of the most visually-influential and important films ever made — as well as one of the most profitable. Becoming the first film ever screened at the White House, Birth will only deepen President Woodrow Wilson‘s racism. It will also spark a renewal of the Ku Klux Klan at Stone Mountain, Georgia, and a disturbing rise in lynchings across America.

Directed by D. W. Griffith, a confederate veteran’s son, The Birth of a Nation features cinematic innovations that have become so routine in our visual culture that we barely notice them today: Griffith inter-cut scenes to create action sequences, used night-shots, alternated between wide ‘establishing’ shots and closer shots to create vast narratives, and challenged audiences with the world’s very first ‘feature length’ production — three hours — at a time when most films were less than twenty minutes long.

Whereas Birth’s warped, racist revision of American history was almost unnoticeable to many whites in the United States of 1915, it is necessarily the first topic of any contemporary introduction. For despite Griffith’s advanced visualization techniques, some elements of the film are otherwise incomprehensible to a modern audience: Griffith has white actors performing the scripted roles in blackface, often with actual Negroes serving as extras in the background. During the final act, white Union soldiers defending the purity of white women from a ravenous mob of sex-crazed black men raise their rifle butts in the air to dash their charges’ brains out and ‘save’ them from being raped — at which point, the Ku Klux Klan heroically rides to their rescue.

When he was sworn in as Vice President of the new Confederate States of America, Alexander Stephens acknowledged the central cause of the war was a southern defense of their ‘peculiar institution’:

With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature, or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system. The architect, in the construction of buildings, lays the foundation with the proper material — the granite; then comes the brick or the marble. The substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it, and by experience we know that it is best, not only for the superior, but for the inferior race, that it should be so.

But after losing the Civil War through predictable material and manpower shortages, southerners invented a myth of the ‘lost cause’ which excused their aggressive war of oligarchy as a defense of Christian civilization and conveniently elided any mention of slavery as their cause. With the collapse of postwar Reconstruction, the original Klan systematically murdered and oppressed anyone or anything, black or white, which might contradict this mass delusion. United Daughters of the Confederacy, an organization born in 1894 and dedicated to propagating the ‘lost cause’ myth, raised funds to put a statue of a confederate soldier outside every county courthouse in the South; meanwhile, the hundreds of thousands of white and black southerners who turned against the confederacy and fought for the union were purposefully forgotten…when they weren’t condemned as traitors.

“My object is to teach the north, the young north, what it has never known — the awful suffering of the white man during the dreadful Reconstruction period,” Thomas Dixon once said during an intermission of his play. “I believe that Almighty God anointed the white men of the south by their suffering during that time…to demonstrate to the world that the white man must and shall be supreme.”

The first third of Griffith’s film presents that false, yet still-widespread view of the Civil War as the result of northern aggression rather than the product of an expansionist, repressive South. Portraying the war itself, the second third of the film is actually the most brilliant in technical and storytelling terms; practically every large battle scene filmed since 1915 contains some inspiration from Griffith’s work. Only in the last four reels, which portray the postwar Reconstruction period as a sinister conspiracy of northern carpetbaggers to destroy the south by encouraging black men to rape and forcibly marry white women, does The Birth of a Nation graduate from mere historical revisionism to disgusting racial slander and sickening, violent white supremacy.

We sometimes forget that free speech was hardly as absolute in America a century ago as it is today; books, magazines, and other media were routinely censored by the US Postal Service under the Comstock Laws. Not until 1933, when the United States Supreme Court upheld freedom of expression in the case of James Joyce’s novel Ulysses, did creators enjoy any presumption of artistic freedom. Indeed, Griffith chose to use white actors wearing obvious blackface partly in order to avoid censorship, for his white audiences would have been horrified to see actual Negro men ravishing white women on the screen. So we should not be surprised that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People campaigned to have the film banned, even succeeding in a few locations.

Yet the overall effect of Griffith’s film is to worsen American race relations, especially when white northern audiences uncritically accept its warped narratives. In the words of Professor Thomas Cripps, Birth “is at once a major stride for cinema and a sacrifice of black humanity to the cause of racism.” Writing a definitive review in 2003, legendary film critic Roger Ebert says:

As slavery is the great sin of America, so “The Birth of a Nation” is Griffith’s sin, for which he tried to atone all the rest of his life. So instinctive were the prejudices he was raised with as a 19th century Southerner that the offenses in his film actually had to be explained to him. To his credit, his next film, “Intolerance,” was an attempt at apology. He also once edited a version of the film that cut out all of the Klan material, but that is not the answer. If we are to see this film, we must see it all, and deal with it all.

When African American men respond to their country’s call for troops in 1917, Griffith’s themes of racial tension, white supremacy, and sexual paranoia will be reprised in riots, lynchings, and controversy. Many postwar monuments will offer separate listings of white and colored dead. America was already a very racist country in 1915, but thanks to Dixon and Griffith, matters will now become even worse.