Another cross-post from the Great War Blog, a daily diary of your modern world being born in blood and fire.

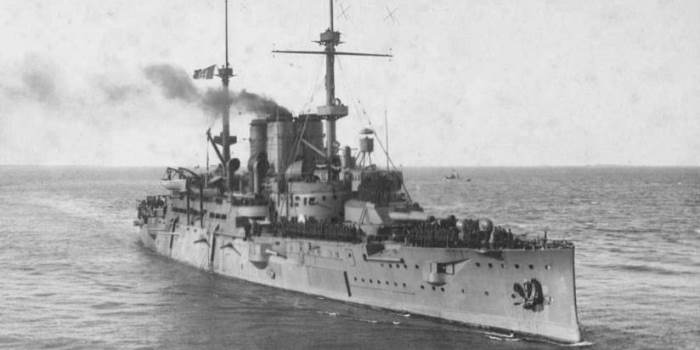

Just after 8 AM yesterday in busy Brindisi harbor, located on the ‘heel’ of Italy’s ‘boot,’ the hot air was split by a sudden blast from the Benedetto Brin, a pre-dreadnought battleship named for the naval engineer who revitalized the Italian Navy in the late 19th Century. According to one senior officer who witnessed the blast, the rear turret was thrown into the air by the explosion, which ripped through the back half of the ship in a sickening shudder of steel and heat, exposing half of the gun tower before the entire gun-stack fell over into the sea. This remarkable sight was the salvation of nearby ships, as it directed the force of the blast upwards rather than outwards.

The tremendous detonation consumed the contents of the rear ammunition compartment, sending a mushroom cloud of smoke into the air while instantly killing hundreds of sailors and splitting the hull wide open. By the time her sister ship Regina Margherita and the rest of the anchored flotilla had even begun to respond, the ship’s keel had already settled on the soft, muddy bottom of the channel, and more than half the Benedetto Brin‘s crew were dead. In all, 454 of the 841 Italian sailors aboard are killed in the disaster, including those who later succumb to injuries from the blast and heat and shock. Recovery and accountability operations will determine that the bodies of 369 men are either disintegrated or unrecognizable — a gruesome task.

The event has shaken the entire city of Brindisi, both literally and figuratively, as a three-day mourning period is declared. Today, the first funeral is held for the deceased, and as they are laid to rest, street speculation is outpacing factual investigation of causes. The official report on the annihilation of the Benedetto Brin will make no determinations, instead posing a number of alternate theories. These include sabotage by a ‘false priest’ using the Catholic church as diplomatic cover to commit an act of sabotage, or a double agent in the Italian Navy, or an accidental ignition of ammunition. No evidence is ever found to link the Central Powers with the sinking of the Benedetto Brin; no U-boats were in the channel, for the anti-submarine net at the harbor mouth remained unbroken. Yet even a century later, enemy espionage is by far the most commonly-cited explanation for what was almost certainly an accident.

It’s not as if the Benedetto Brin is the only battleship to suddenly become a bomb during the Great War. Ten months ago, the HMS Bulwark suffered a very similar catastrophic explosion at almost the same time of day, when many sailors smoke after-breakfast cigarettes. Like the Bulwark, Benedetto Brin‘s 12-inch guns used cordite propellant charges — basically, bundled spaghetti-like strands of gunpowder and colloidal cotton stored in bags. The Benedetto Brin‘s ammunition compartment was adjacent to the engine room, and the Italian Navy’s official report does mention the possibility that old ammunition ‘cooked off,’ which is also the most probable explanation for the Bulwark explosion.

Nor is the phenomenon of exploding battleships limited to accidents. The old French battleship Bouvet, which struck a mine during the March 18th naval assault on the Dardanelles and then sank from a secondary explosion in her ammunition compartment, went down in just moments with 610 of 650 hands still on board. Obsolete, the Benedetto Brin has been rated more of a battlecruiser than a battleship for years because it was never heavily-armored, substituting speed for steel, but her death suggests that these designs might not be safe at any speed.

Indeed, there will be no vengeance for the Benedetto Brin. While steaming off Vlorë amid heavy seas in December 1916, her sister ship Regina Margherita strikes a pair of German-built sea mines, sinking quickly after yet another great explosion. Of the 945 men on board, all but 270 are killed, including the commander of the Italian Albania Expeditionary Corps. But that will be months after the indecisive Battle of Jutland, in which British fighting ships also explode from hits that set off propellant stacks stowed unsafely in corridors to speed up the rate of gunnery. Having helped bring about the Great War by creating balance-of-power tensions, the great battleships will not have a significant role in bringing the war to a conclusion, and from a century’s distance, they seem more dangerous to their crews than their enemies.