I’m back from book leave and you’ll be seeing me every weekday here. Below is another sample from my daily blog about the First World War, a narrative of our modern world being born in blood and fire a century ago. The first day of 1915 brought an event which remains controversial — and strongly suggests the ‘Age of Terror’ is much older than September 11, 2001.

01 January 1914 – Asymmetric

Early this morning, the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Formidable is torpedoed by U-24 as she steams off the coast of southwest England. Hit again as she founders, 537 of her 780 crewmen cannot be rescued in the rough seas. She is the third British battlewagon to be lost in the war, and the second to asymmetrical enemy action. Audacious was sunk by a mine in October, an event which so shocked the Admiralty that the London press is still absurdly covering up the disaster.

Having lost his global cruiser fleet to British maritime domination, the Kaiser will soon answer the British blockade with a U-boat campaign of alarming effectiveness. And why not? His small, relatively-inexpensive submarines and minelayers have already accounted for more English battleships than his own pricey High Seas Fleet. The prewar inequality of battleship firepower is not resolving into the long-expected gunnery duel, but rather into a prolonged standoff of competing blockades conducted with smaller craft.

Ours is an age of asymmetric violence, when states and nonstate actors use the smallest means to disable the largest of foes, while states seek to shed risk in their responses. Military imbalance is thus addressed through fear: German bombs and shells deliberately target civilians and cultural sites to inspire fear and terror, hoping to break the will of enemy nations. German troops killed thousands of Belgian and French civilians in the opening weeks of the war to suppress the nonexistent guerrilla fighters, or Francs-tireurs, they feared would shoot them in the back without the courtesy of wearing uniforms.

We flatter ourselves today by thinking that we invented these issues in 2001. In fact, we have been living in the ‘Age of Terror’ for a very long time.

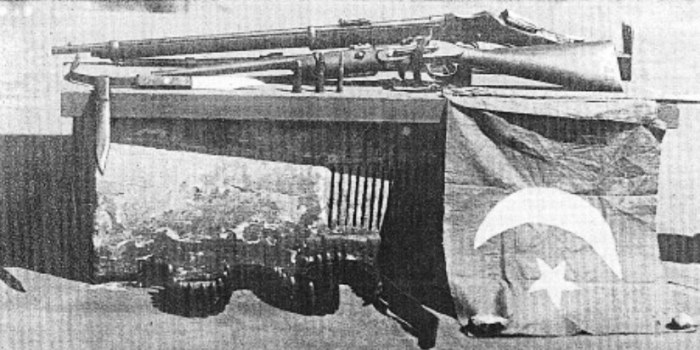

Underlining that point, just a few hours after the Formidable‘s destruction two men lie in wait on an embankment overlooking the railroad between Broken Hill and Silverton in New South Wales, Australia. As the annual New Year’s Day train approaches bearing 1,200 passengers, 60-year old Badsha Mohammed Gool and 40 year-old Mullah Abdullah rise to take firing positions. Gool’s ice cream cart, which the two men used to transport their rifles and ammunition, sits close by, next to their makeshift Ottoman flag (see photo at top). They are Afghans from what is now Pakistan, part of a small community that arrived in the 1890s to handle the camel trains that work mines here in the remote outback.

Riding in open-topped ore cars, the picnickers assume that the turbaned men are just cameleers out rabbit-hunting — until the first of forty bullets they fire kills 17-year old Alma Cowie. Screams split the late morning air. Eight other passengers are hit; one more dies of his wounds before the train pulls over at a siding to call the police, who immediately contact the local army post for reinforcements.

Returning towards their homes at the West Camel camp, Gool and Abdullah kill a witness named Alfred E. Millard who had taken shelter in his hovel. Spotted by police near the Cable Hotel, they wound a constable before taking cover among some quartz rocks on Cable Hill. A ninety-minute gun battle with police and soldiers leaves both men dead of multiple wounds and leaves yet another civilian dead who refused to stop chopping wood in the crossfire. Incongruously known as the Battle of Broken Hill, this early example of a modern-day ‘suicide shooting’ remains controversial in Australia a century later, where the current government has refused to support any commemoration of the event.

Gool had claimed at times to have served in the Ottoman Army. Now, in a note tucked under his belt, he cites the November fatwa of jihad from Constantinople to justify his murderous spree. “I must kill your men and give my life for my faith by order of the Sultan,” he says. Abdullah’s note also acknowledges these motivations, but emphasizes his “grudge against Chief Sanitary Inspector Brosnan,” who recently fined Abdullah for operating an unlicensed butcher’s shop. “It was my intention to kill (Brosnan) first. Beyond this there is no enmity against anybody, and we informed nobody.”

In fact, Brosnan appears to have cited Abdullah’s illegal abattoir, where he had slaughtered animals according to the halal rules for the consumption of local Muslims, more than once. Cultural insensitivity and the Butchers Trade Union monopoly have compounded Abdullah’s resentment at the systematic exploitation and oppression of his Islamic ummah (community), which is forced to live in a segregated shanty-town and work for inferior wages. Abdullah had already stopped wearing a turban some years before due to teasing and rock-throwing by local children, never quite overcoming his anger. Yet contemporary investigators conclude that Gool was the stronger personality, and that he leveraged Abdullah’s simmering rage to recruit him for the attack.

The incident is exactly what the Kaiser wanted to happen when his diplomats convinced the Turkish government to issue the fatwa. This deliberate invocation of religious violence against the British Empire is not restricted to Islam, either, for German agents are currently stirring Hindus and Indian nationalists to rise up against their British lords, too. Berlin propagandists even make a ham-handed attempt to claim responsibility for Gool and Abdullah’s actions, proclaiming the mines at Broken Hill to be under occupation. So perhaps it is not surprising that, within 24 hours, attention and outrage have shifted entirely away from the Afghan camel drivers’ camp and towards the local German community.

The Broken Hill German Club is burned to the ground. Locals even cut the firehoses when officials try to put out the flames. The next day, mine managers fire every employee deemed an ‘enemy alien’ under the 1914 Commonwealth War Precautions Act, while six Austrians, four Germans, and one Turk are immediately run out of town by an angry mob. Required to register with police, all other German nationals are eventually interned at Holsworthy Concentration Camp.

We like to blame the Great War on sectarian tensions, but in the war’s sixth month public attitudes have actually hardened. There is national and religious hatred now where none existed in August. Strangely, bloody battles have not fanned the intolerant flames of war quite like asymmetrical attacks on civilians, who have still suffered in far lower numbers than those in uniform. It has also been a season of broken loyalties and high treason, so the Battle of Broken Hill deepens wartime paranoia about espionage and insurrection. Love of freedom is already giving way to the permanent emergency of insecurity. We have more to learn from these days than we probably care to admit.